Paving pathways for India’s labour force

According to the PLFS report for 2021-22, the Indian worker population ratio for ages 15 and above is only 52.9%[1]. This is much lower compared to other countries, such as China (80%) and Japan (70%), during periods of rapid economic growth[2]. Further, 26.8% of the labour force is employed in casual work, with no fixed income or job security[3]. Most workers don’t have high productivity opportunities available to them – the average wages are Rs. 366 per day for casual labour, and even lower in agriculture at Rs. 296 per day [4]. Even though the social security framework of Jan Dhan – Aadhar – Mobile (JAM) has provided protection against extreme deprivation, insecurity amongst the working class remains high due to the lack of a stable income. There is a pressing need to create better jobs for India’s large working age population and improve their standard of living.

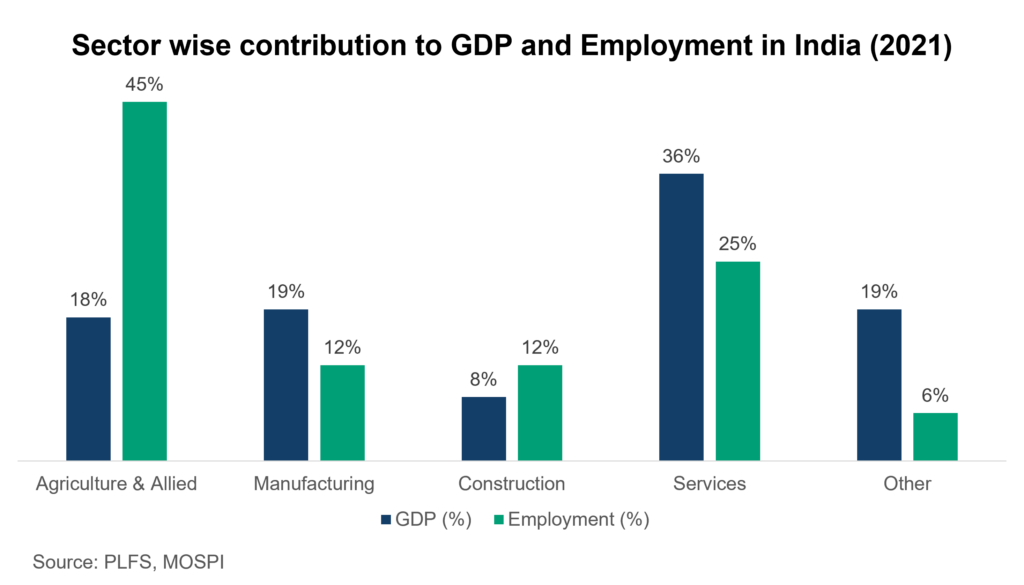

Data from even India’s most industrialised states (Maharashtra, Karnataka, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Telangana) show that we haven’t gotten very far in industrialisation. Agriculture and allied sectors in these states employ ~43% of the population but contribute only ~11% to their economy. In contrast, the manufacturing sector employs ~15% and contributes ~20% to the economy[5]. This is a clear indication that even in the most industrialised states in India, the workforce is stuck in low productivity sectors. Overall, ~24 crore people in India are employed in agriculture, and getting just half the population out of agriculture in India would require us to create 12 crore new job opportunities. Additionally, the country has a large untapped female labour force. In 2005, 30% of women in India were in the paid labour force, and this number has come down to 19% in 2021. Getting back to 30% would imply creating 8 crore additional jobs for our women.

Throughout history, manufacturing has consistently been the established route to achieving economic progress and job creation. However, according to some commentators, including former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan, India should not look to replicate China’s success in manufacturing, but should rather focus on its strengths – which he says are in the services industry[6]. Given the success of India’s IT sector, could India leapfrog to IT services to fuel the expansion of the working class, bypassing manufacturing?

Where will the jobs come from?

The service sector has indeed driven much of our early growth in the late 90s and 2000s. However, while we should continue to facilitate growth in services exports, we will hit diminishing returns. India is already the leading sourcing destination across the world, and expanding market share significantly beyond this will prove to be very challenging, especially in the current climate where AI will compete with Indians [7]. In 2022, India’s IT sector generated an additional 4.5 lakh new jobs[8]. According to NASSCOM data, even when considering the wider scope of the industry, encompassing tasks like call centres, the overall employment amounts to 45 lakhs[9]. This is a tiny fraction compared to India’s substantial workforce. Can the rest of the services sector create the quantum of jobs this country needs along with productivity driven income boosts for the working class population? Further, these areas are skill intensive and do not employ vast numbers of people.

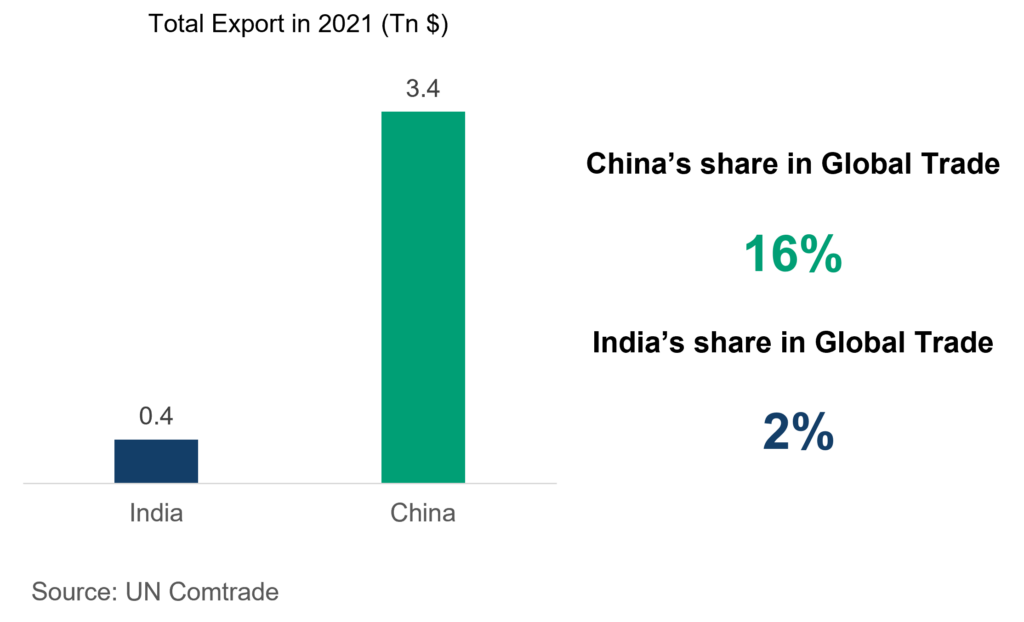

In 2021, India’s share of exports in global merchandise trade was only 2%[10], and we had ~12 crore industrial employment. On the other hand, China’s share of exports in global trade is 16% with ~21 crore industrial employment[11].

Given that India accounts for 20% of the world’s population, we should aim to capture at least 10% of the global trade by capitalising on our strength and focusing on increasing our share in labour intensive exports. This could potentially scale to 5 times more employment in the manufacturing sector as well.

Has India missed the bus for manufacturing?

It is believed by many that the golden age of manufacturing has passed, and that China was probably the last major economy to gain from making itself a manufacturing and export powerhouse, and now the world is simply incapable of digesting another export-led economy like China. However, this is simply not true. In the past decade itself, countries like Vietnam have had manufacturing at the epicentre of their growth.

Vietnam’s manufacturing miracle is the most recent evidence to support that establishing large scale manufacturing for exporting to the world market can catalyse economic growth and employment generation in a country. By the 2000s, China had already established its dominance in electronics manufacturing, producing for the largest market players including Apple, HP, Dell, and Samsung[12]. However, firms such as Samsung were seeking to reduce their reliance on China due to its rising labour costs and geopolitical pressures – a trend that continues today[13]. Vietnam crucially leveraged its cheap labour and established a favourable business-friendly environment for large-scale manufacturing. These policies attracted Samsung, the 2nd largest mobile phone producer at the time, to steadily move its production into Vietnam[14]. In 2008, Vietnam granted Samsung its first Investment Region Certificate (IRC) with a registered investment capital of 670 million USD[15]. As a result, Vietnam swiftly transitioned into a global manufacturing hotspot, diversifying its exports, and enhancing its economic resilience[16]. This marked a pivotal moment in the country’s economic trajectory, transforming its primarily agrarian economy into a thriving manufacturing hub.

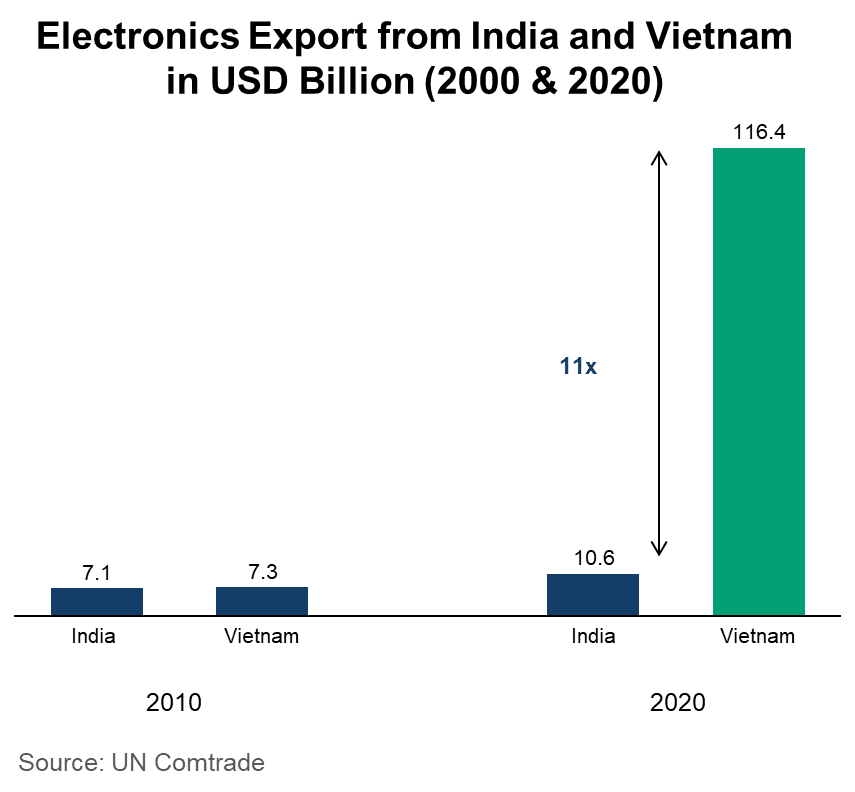

In 2010, India and Vietnam’s electronics exports stood at ~7 billion USD, however in the next 10 years Vietnam’s electronics exports grew at the rate of 32% annually, whereas India’s electronics exports grew only at the rate of 4%. By 2020, Vietnam’s electronics exports stood at ~116 billion USD, which was 11 times that of India’s exports in electronics.

Prior to Vietnam’s shift in focus to export led manufacturing, and Samsung’s arrival, Vietnam’s economy was struggling with a low GDP growth rate, underdeveloped infrastructure, and limited foreign investment. The economic landscape was in dire need of a catalyst for growth, which Vietnam achieved by convincing Samsung to establish manufacturing facilities in the country. This reflected in employment numbers, since between 2010 and 2020, Vietnam’s industrial jobs (manufacturing + construction) grew at a CAGR of 4%. This clearly established that even now a manufacturing cluster empowered by economies of scale and well-equipped plug-and-play infrastructure can create massive employment for a nation.

Blueprint for launching large scale manufacturing in India

Until now, India has severely underperformed in creating a cluster led development model. In 2022, India had 272 operational Special Economic Zones (SEZs) that contributed USD 61 Billion to merchandise exports from India [17]. In comparison China has been able to achieve ~5x in exports from just Shenzhen, which contains China’s largest SEZ and is approximately the same size as the combined area of all the Indian SEZs[18]. According to a CAG report that evaluated the performance of SEZs in 2013, the actual employment in SEZs in 12 Indian states had fallen short by ~93% and investments were ~60% lesser than the projected amounts. It was also noted that the level of exports, which are considered to be critical to the success of an SEZ, were 75% lesser than the projected amount[19].

India’s SEZs showcase both the potential the country has for creating a large scale manufacturing cluster as well as highlights the shortcomings that need to be fixed. For example, the Brandix India Apparel City (BIAC) in Andhra Pradesh is built on a “fibre to store” concept, where all processes, right from raw material procurement to final product shipment, are available on site[20]. By ensuring easy access to an ecosystem of suppliers and customers, the apparel city model has created 21,000 jobs. Roughly 76% of the workers here are women, and the social infrastructure provided within the city, such as crèche and transport services, facilitates their active participation. However, as per the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that was signed between them and the Andhra Pradesh state government, BIAC had assured to create 60,000 manufacturing jobs. In over a decade of its establishment, it has managed to create only 1/3rd employment that was promised. What would it take for turning this partial success story of Indian manufacturing into a complete victory?

India’s fragmented approach to cluster development hampers its ability to achieve scale and competitiveness. BIAC was allotted 1000 acres of land to run its operations, which is almost 7 times lesser than the Shenzhen SEZ. To manufacture at scale, we must explore strategies such as expanding existing clusters, focusing on core infrastructure development, and optimizing land acquisition. The lack of planned infrastructure in Indian industrial regions is also a major hindrance to attracting large-scale manufacturing. In fact, BIAC stated that inadequate infrastructure, including a four-lane road connecting the highway and failure to provide uninterrupted power supply to the apparel city was the main reason for being unsuccessful in generating employment[21].

To tackle this, we must focus on four key domains for infrastructure development: basic infrastructure, common industrial infrastructure, export infrastructure, and social infrastructure. Private partnerships can play a role in developing this infrastructure. Further, incentives should be strategically targeted to sectors and regions with the potential to develop sustainable ecosystems. Timely delivery of such incentives is crucial to building trust among investors, and investment promotion agencies should be involved from the beginning to co-create regions based on investor requirements. Finally, we need a more novel approach to governance and regulations within industrial clusters. Reducing regulatory burdens and fostering a favourable business environment are essential to attracting international investors. Ease of doing business can be improved by streamlining compliance procedures and empowering an inter-agency authority to expedite decision-making and clearances[22]. Creating governance bodies to promote cluster driven growth, such as the Philippine Economic Zone Authority, or the Bangladesh Export Processing Zone Authority, can work to assuage investors’ concerns and needs efficiently.

The time is now ripe for India to become a major manufacturing player, and the present geopolitical system has given us the right opportunity. Given the sheer size of India, we should ideally be in a position create at least 5 Vietnams within India! This will only be possible if we can successfully create a globally competitive ecosystem in manufacturing.

[2] World Development Indicators – World Bank

[6] Rajan on China’s Model of Manufacturing – The Economic Times

[7] What Does AI Imply for India’s Growth – Live Mint

[8] IT generated 4.5 lakh jobs in 2022 – Times Now

[9] A stunted middle class: Role of the manufacturing, informal sectors – Times Now

[12] Why Did China Emerge as the Heart of Tech Supply Chain – Kearney

[13] Samsung a Case Study on Leaving China – The Wall Street Journal

[14] Global Market Share by Mobile Manufacturers – Statista

[15] Samsung Playing Long Game in Vietnam – Forbes

[16] Samsung Playing Long Game in Vietnam – Forbes

[18] What India needs to create successful economic zones – Live Mint

[19] Performance of Special Economic Zones – CAG Report

[20] Evaluating Impact of SEZs in India Report – PwC

[21] Apparel city may remain a pipe dream – TOI

[22] (Un)ease of Exporting Merchandise from India – FED Blog