The Indian government aims to achieve USD 2 trillion total export by 2030, one trillion each in merchandise and services[1]. India also needs to create massive employment to tap into its underutilised workforce of ~12 crore people in the coming years[2]. In order to achieve these targets, we need to improve our manufacturing competitiveness and make use of economies of scale. One of the biggest challenges of large-scale manufacturing is sourcing a large workforce at one place. Very often, these workers are migrants, given the realities of population density and scale requirements. There is an important ‘chicken and egg’ attribute to worker housing for migrant workers – until the industry comes up in an area, there is no need for housing, and until there is housing, it doesn’t make sense to set up industry.

Worker housing must be regarded as ‘infrastructure’ for rapid large-scale industrialisation. It has important distributional consequences – if the factory is located far away from worker homes, time and money gets spent on travel, effectively reducing real wages. Given our restrictive zoning and building laws, market responses are also prevented from being optimal. In fact, certain parts of Delhi, knows as the lal dora (village) areas are exempt from restrictive building bye laws and construction norms of the Delhi Municipality Act. However, even in these areas, owners are not allowed to build freely enough; they are required to obtain an NOC from the local office of the Land and Revenue Department[3]. Eventually, a common response to these restrictions on buildings is the spontaneous emergence of slums.

This situation can be seen near NCR’s garment manufacturing clusters, where informal, unauthorised, multi-storey settlements or ‘colonies’ of rooms were constructed and given to migrants for rent. A study[4] that was conducted revealed that these workers’ ‘colonies’ ranged from 30 to 100 rooms, costing Rs 3000–3500 a month, which is a little less than half the wage of a garment worker. In these accommodations, water was available for only two hours daily, illegally siphoned from the city’s supply, while electricity was diverted from local powerlines and charged to tenants at Rs 8 per unit, twice the usual cost. These living conditions were inevitable for migrants that wanted to work in NCR. This accommodation was also the cheapest available, located at a walking distance of 15-30 minutes from industrial clusters[5].

A dedicated effort to improve industrial worker housing can help resolve these issues. The first step to achieve this would be through optimising utilisation of land through modifications in building bye laws.

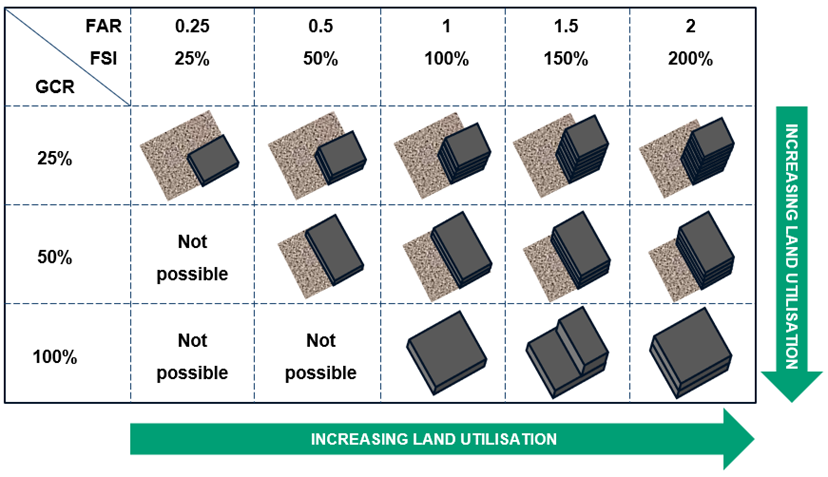

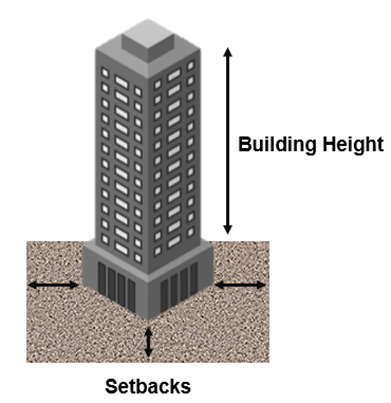

Building bye laws or regulations are the set of rules and guidelines, typically developed at the state-level, and in some states enforced at the local body level, that oversee the construction and development of buildings and structures. These regulations outline the permissible land uses and zoning restrictions, thereby affecting efficient land utilisation. The major regulatory instruments include ground coverage ratio (GCR)[6], floor area ratio (FAR)[7], setback requirements, height limitations, parking and amenities requirements. FAR and GCR regulate the extent of building coverage on a plot. A higher GCR indicates a higher percentage of the plot covered, i.e., more horizontal growth, and higher FAR allows higher vertical growth.

Even if a state has unlimited FAR, a building’s vertical growth can be restricted with specified height requirements. Setbacks define the minimum distance to be maintained from property lines, roads, and neighbouring properties, which ensures that the building is receiving adequate sunlight, ventilation, greenery, and vehicular access. But a very high setback can lead to wastage of space.

The remaining available land is further encumbered by mandatory parking requirements which is unnecessary for industrial housing given that most industrial workers are unlikely to own cars.

If we aspire to establish clusters on a scale comparable to those in China, it is essential to provide accommodation for a large number of workers in close proximity to these industrial facilities that is efficient as well as liveable. Currently, no state in India has separate regulations for industrial worker housing.

Singapore is one of the countries that has separate act for migrant housing called the Foreign Employee Dormitories Act 2015[8] and differential building regulations for workers’ dormitories[9]. Tuas View Dormitory[10] is one of the largest housing complexes in Singapore for migrant workers in the marine, construction and manufacturing sector which can accommodate 16,800 people. It covers a total build up area of ~1,18,000 sq.m, for which it requires total land area of ~27,000 sq.m. Accommodating the same number of people in India’s most industrialised states would take on average 3 times more land[11]. In most large cities around the world, the FAR varies from 5 to 15[12] in industrialised areas. The southern tip of New York City’s Manhattan has an FAR of 15, one of the highest in the world, which is permitted both for residential, commercial and industrial purposes. In contrast, the extraordinarily low FAR in most Indian cities have led to a shortage in housing. For instance, the maximum permitted FAR is only 1.33[13] in Mumbai’s central business district. Clearly, the existing residential building regulations are not targeted to meet the housing needs of large scale, globally competitive industry.

Better land utilisation is a solution to only one part of the problem, the other is the need for operating efficiency and adequate return on capital. Private players would be the best equipped to operate and maintain accommodations of such a large scale. However, cost of capital is high, and rates of returns provided by industrial projects are well below the market rates for the same risk[14], making it unattractive for private players to enter the space. Presently, government schemes on affordable housing such as the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY) are mainly for outright purchase and assist in building of homes. These schemes are not targeted at industrial rental housing. Globally, many countries have recognized that home ownership at the unskilled/semi-skilled level is not the ideal solution to their housing troubles. A similar situation was solved by Singapore in the 1960s, by the Housing and Development Board that built rental units at a time of housing crisis. Many people argue that Singapore’s economic success is actually built on a foundation of affordable housing for its citizens.

How can India draw insights from global best practices to provide affordable industrial housing to workers? Firstly, to enable large scale and well-maintained housing, the government should develop differential bye laws for worker housing by integrating best-in-class regulations. This can bring down land required by up to 85%[15]. These worker accommodations should be built near manufacturing premises to cut down on travel cost and time for workers. Secondly, a vibrant rental market needs to be developed. In fact, the government launched the Affordable Rental Housing Complex (ARHC) scheme in June 2020 as a sub-scheme under the PMAY scheme to provide decent rental housing for the urban poor near their work sites. However, project proposals under ARHCs were considered only up to March 2022, since this scheme was positioned towards returning migrants during the Covid-19 pandemic. The scope of housing schemes should be expanded, or a separate scheme may be developed to provide interest subvention for industrial housing rental projects.

[3] Lal Dora Certificate and Its Significance in India

[4] Beyond the Dormitory Labour Regime – Sage Journals

[5] According to Delhi government’s Economic Survey for 2020-21, 6.75 million people lived in poor housing in low-income settlements only in New Delhi, which included 695 slum settlements and 1,797 unauthorised colonies

[6] GCR is represented as the percentage of ground area covered by buildings and other impervious surfaces compared to the total area of the lot.

[7] FAR is a ratio calculated by dividing a building’s total floor area by the amount of land it sits on.

[9] Singapore Urban Redevelopment Authority

[11] FED Analysis

[12] Impact of Land Use Regulations: Evidence from India’s Cities

[15] Author’s calculation based on building bye laws